I just parachuted in on (and heli'd out of?) the Beyond the Genome conference in Boston. I gave a very brief workshop on using EC2 for sequence analysis, which seemed well received. (Mind you, virtually everything possible went wrong, from lack of good network access to lack of attendee computers to truncated workshop periods due to conference overrun, but I'm used to the Demo Effect.)

After attending the last bit of the conference, I think that "the cloud" is actually a really good metaphor for what's happening in biology these days. We have an immense science-killing asteroid heading for us (in the form of ridiculously vast amounts of sequence data, a.k.a. "sequencing bonanza" -- our sequencing capacity is doubling every 6-10 months), and we're mostly going about our daily business because we can't see the asteroid -- it's hidden by the clouds! Hence "cloud computing": computing in the absence of clear vision.

But no, seriously. Our current software and algorithms simply won't scale to the data requirements, even on the hardware of the future. A few years ago I thought that we really just needed better data management and organization tools. Then Chris Lee pointed out how much a good algorithm could do -- cnestedlist, in pygr, for doing fast interval queries on extremely large databases. That solved a lot of problems for me. And then next-gen sequencing data started hitting me and my lab, and kept on coming, and coming, and coming... A few fun personal items since my Death of Sequencing Centers post:

we managed to assemble some 50 Gb of Illumina GA2 metagenomic data using a novel research approach, and then...

...we received 1.6 Tb of HiSeq data from the Joint Genome Institute as part of the same Great Plains soil sequencing project. It's hard not to think that our collaborators were saying "So, Mr. Smarty Pants -- you can develop new approaches that work for 100 Gb, eh? Try this on for size! BWAHAHAHAHAHAHA!"

I've been working for the past two weeks to do a lossy (no, NOT "lousy") assembly of 1.5 billion reads (100 Gb) of mRNAseq Illumina data from lamprey, using a derivative research approach to the one above, and then...

...our collaborators at Mt. Sinai Medical Center told us that that we could expect 200 Gb of lamprey mRNA HiSeq data from their next run.

(See BWAHAHAHAHAHAHAHA, above.)

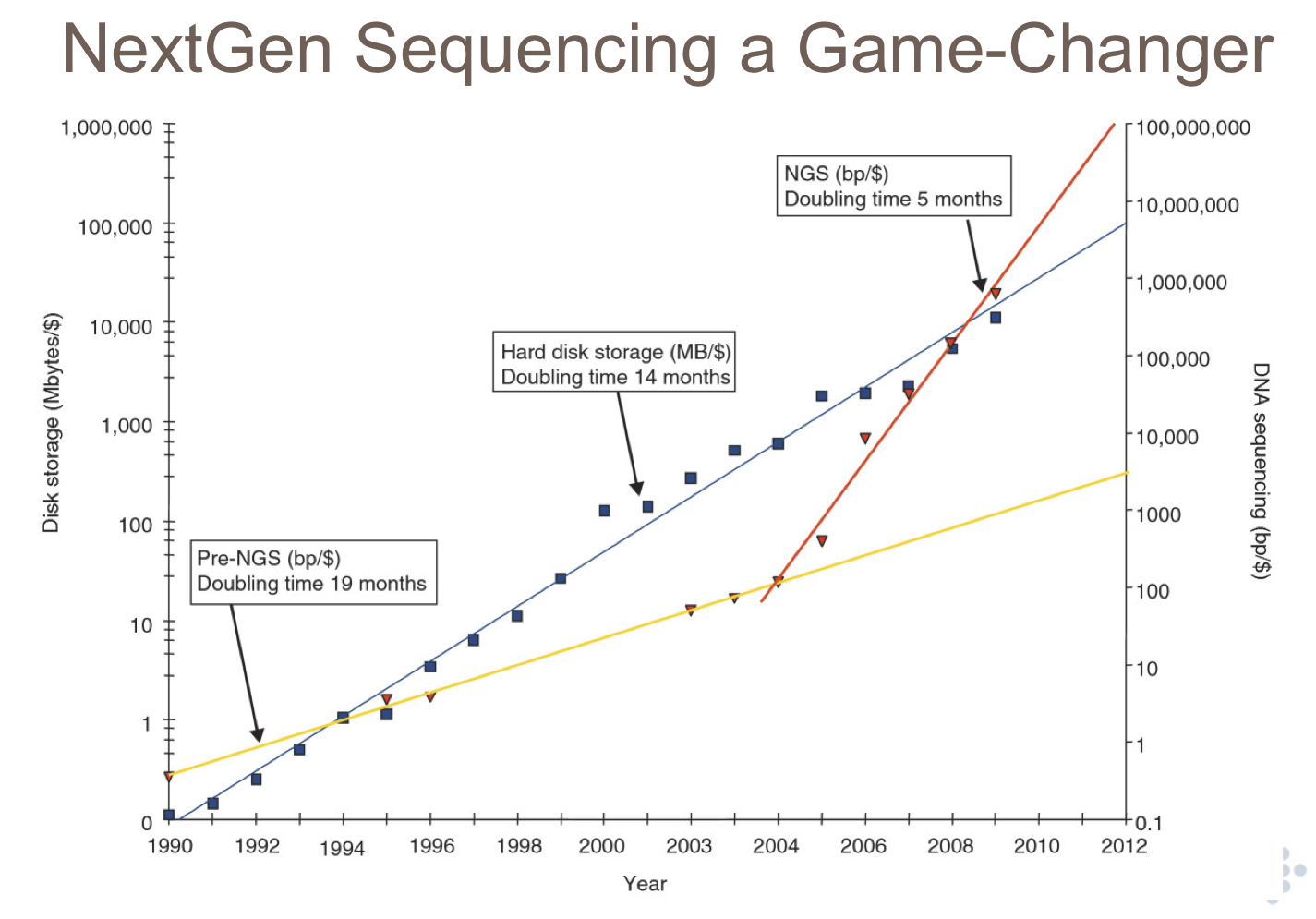

Honestly, I think most people in genomics, much less biology, don't appreciate the game-changing nature of the sequencing bonanza. In particular, I don't think they realize the rate at which it's scaling. Lincoln Stein had a great slide in his talk at the BTG workshop about the game-changing nature of next-gen sequencing:

The blue line is hardware capacity, the yellow line is "first-gen" sequencing (capillary electrophoresis), and the red line is next-gen sequencing capacity.

It helps if you realize that the Y axis is log scale.

Heh, yeah.

Now, reflect upon this: many sequence analysis algorithms (notably, assembly, but also multiple sequence alignment and really anything that doesn't rely on a fixed-size "reference") are supra-linear in their scaling.

Heh, yeah.

We call this "Big Data", yep yep.

At the cloud computing workshop, I heard someone -- I won't say who, because even though I picked specifically on them, it's a common misconception -- compare computational biology to physics. Physicists and astronomers had to learn how to deal with Big Data, right? So we can, too! Yeah, but colliders and telescopes are big, and expensive. Sequencers? Cheap. Almost every research institution I know has at least one, and often two or three. Every lab I know either has some Gb-sized data set or is planning to generate 1-40 Gb within the next year. Take that graph above, and extrapolate to 2013 and beyond. Yeah, that's right -- all your base belong to us, physical scientists! Current approaches are not going to scale well for big projects, no matter what custom infrastructure you build or rent.

The closest thing to this dilemma that I've read about is in climate modeling (see: Steve Easterbrook's blog, Serendipity). However, I think the difference with biology is that we're generating new scientific data, not running modeling programs that generate our data. Having been in both situations, I can tell you that it's very different when your data is not something you can decline to measure, or something you can summarize and digest more intelligently while generating it.

I've also heard people claim that this isn't a big problem compared to, say, the problems that we face with Big Data on the Internet. I think the claim at the time was that "in biology, your data is more structured, and so you haff vays of dealing with it". Poppycock! The unknown unknowns dominate, everyone: we often don't know what we're looking for in large-scale biological data. When we do know, it's a lot easier to devise data analysis strategies; but when we don't really know, people tend to run a lot of different analyses, looking looking looking. So in many ways we end up with an added polynomial-time exploratory computation scaling (trawling through N databases with M half-arsed algorithms) on top of all the other "stuff" (Big Data, poorly scaling algorithms).

OK, OK, so the sky is falling. What do we do about it?

I don't see much short-term hope in cross-training more people, despite my efforts in that direction (see: next-gen course, and the BEACON course). Training is a medium-term effort: necessary but not all that helpful in the short term.

It's not clear that better computational science is a solution to the sequencing bonanza. Yes, most bioinformatics software has problems, and I'm sure most analyses are wrong in many ways -- including ours, before you ask. It's a general problem in scientific computation, and it's aggravated by a lack of training, and we're working on that, too, with things like Software Carpentry.

I do see two lights at the end of the tunnel, both spurred by our own research and that of Michael Schatz (and really the whole Salzberg/Pop gang) as well as Narayan Desai's talk at the BTG workshop.

First, we need to change the way analysis scales -- see esp. Michael Schatz's work on assembly in the cloud, and (soon, hopefully) our own work on scaling metagenomic and mRNAseq assembly. Michael's code isn't available (tsk tsk) and ours is available but isn't documented, published, or easy to use yet, but we can now do "exact" assemblies of 100 Gb of metagenomic, and we're moving towards nearly-exact assemblies of arbitrarily large RNAseq and metagenomic data sets. (Yes, "arbitrary". Take THAT, JGI.)

We will have to do this kind of algorithmic scaling on a case-by-case basis, however. I'm focused on certain kinds of sequence analysis, personally, but there's a huge world of problems out there that will need constant attention to scale them in the face of the new data. And right now, I don't see too many CSE people focused on this, because they don't see the need to scale to Tb.

Second, Big Data and cloud computing are, combined, going to dynamite the traditional HPC model and make it clear that our only hope is to work smarter and develop better algorithms, in combination with scaling compute power. How so?

As Narayan has eloquently argued many times, it no longer makes sense for most institutions to run their own HPC, if you take into account the true costs of power, AC, and hardware. The only reason it looks like HPCs work well is because of the way institutions play games with funny money (a.k.a. "overhead charges"), channeling it to HPC behind the scenes - often with much politicking involved. If, as a scientist, your compute is "free" or even heavily subsidized, you tend not to think much about it. But now that we have to scale those clusters 10s or 100s or 1000s of X, to deal with data 100s or 1e6s of times as big, institutions will no longer be able to afford to build their own clusters with funny money. And they'll have to charge scientists for the true computational cost of their work -- or scientists will have to use the cloud. Either way, people will be exposed to how much it really costs to run, say, BLAST against 100,000,000 short reads. And soon thereafter they'll stop doing such foolish things.

In turn, this will lead to a significant effort to make better use of hardware, either by building better algorithms or asking questions more cleverly. (Goodbye, BLAST!) It hurts me to say that, because I'm not algorithmically focused by nature; but if you want to know the answer to a biological question, and you have the data, but existing approaches can't handle it within your budget... what else are you going to do but try to ask, or answer, the question more cleverly? Narayan said something like "we'll have to start asking if \$150/BLAST is a good deal or not" which, properly interpreted, makes the point well: it's a great deal if you have \$1000 and only one BLAST to do, but what if you have 500 BLASTs? And didn't budget for it?

Fast, cheap, good. Choose two.

Better algorithms and more of a focus on their importance (due to the exposure of true costs) are two necessary components to solving this problem, and there are increasingly many people working on them. So I think there are these two lights at the end of the tunnel for the Big Data-in-biology challenges. And probably there are some others that I'm missing. Although, of course, these two lights at the end of tunnel may be train headlights, but we can hope, right?

--titus

p.s. Chris Dagdigian from BioTeam gave an absolutely awesome talk on many of these issues, too. Although he seems more optimistic than I am, possibly because he's paid by the hour :).

Legacy Comments

Posted by Istvan Albert on 2010-10-14 at 20:21.

I for one believe that the problem will solve itself ... the next breakthrough will come from the technology that generates long, continuous reads that are a lot easier to map and assemble.

Posted by Titus Brown on 2010-10-14 at 21:37.

Istvan, I hear that a lot. I believe that assemblies will improve dramatically with longer reads; I'm also positive that getting 200 Gb of 10kb PE reads is going to break most assemblers.

Posted by Charles McCreary on 2010-10-14 at 22:34.

The HPC issue is getting better! You can now cluster up to 8 dual quad core nehalems with "close to the metal" HVM virtualization on AWS. 64 dedicated cores gets a fair amount done, anything more and you need to ask permission. I've been doing this for the last month with open source Computional Fluid Dynamics (CFD) tools with impressive (to me) results. Although I have 32 cores available in the rack, it won't be long before I will be able to marshal 1024 cores on AWS without special permission. I've built a Django interface to the whole process that handles all the nitty-gritty details. My still unresolved issue is how to visualize/process the gargantuan datasets without downloading them. HTML5?

Posted by Titus Brown on 2010-10-14 at 23:55.

Charles -- yep, that's (going to be) our solution. Web interrogation!

Posted by Deepak on 2010-10-15 at 08:05.

Charles very interested in what you've tried on the cluster compute instances this far. Also getting more than 8 is an email away (well a web form away). More than HTML5, good APIs to the data.

Posted by Titus Brown on 2010-10-15 at 10:45.

Deepak, not sure I completely agree. For exploratory analysis, building an API is often a waste of time; writings scripts that provide a shallow, but investigable, view of output, is much easier and will lead to a better API down the road. cheers, --titus

Posted by Titus Brown on 2010-10-15 at 11:24.

See Chris Dagdigian's talk here: <a href="http://blog.bioteam.net/2010/10/15/commercial-clouds-for- bioinformatics/">http://blog.bioteam.net/2010/10/15/commercial-clouds- for-bioinformatics/</a>

Posted by Rory Carmichael on 2010-10-15 at 15:16.

I like a lot of your post and heard some similar comments from Folker Meyer (http://www.mcs.anl.gov/~folker/) at ECMLS during HPDC this summer. His talk was particularly interesting because he implied that the primary obstacles to bioinformatics are social. He talked a lot about the obfuscated cost of computation at research institutions and showed some pretty terrifying graphs of the cost of large blasts as compared to the cost of sequencing runs. (hint: blast of all reads costs much much more than sequencing those reads for newest sequencing machines) His most interesting point (I thought) was that even when new, better algorithms are developed they aren't used. I don't see this as likely to change very much until we come up with a good pipeline of translating the complexity and correctness proofs from computer science algorithms research into a form that is accessible (and visible) to the biological community.

Posted by Titus Brown on 2010-10-15 at 20:47.

Rory, yep, Folker and I have talked about this, of course. I think the social aspect will be "solved" by the increasing cost of computation. If it's cheap to do a 10,000 hr blast, then why not? Why put the effort into developing and understanding a faster approach? Answer: don't. But as soon as the computation becomes the pain point, you start pushing on efficiency and scalability, and listening more to people who claim to have a solution. The key is to do both good science **and** good computation. That's hard, and most people focus on the former, because in many ways it's easier for them to evaluate. --titus

Posted by Deepak on 2010-10-16 at 12:33.

Titus The way I see it, scripts are a temporary solution, but if the consumer web has taught us anything it is that good APIs (even internal to companies with large quantities of data) are what enables productivity and innovation. Having said that I don't disagree with your statement. Scripts are a good place to start and can inform API design, but API innovation is going to be key.

Posted by Paul Boddie on 2010-10-16 at 13:05.

On the topic of capacity, I don't get the remarks about physics being different, even though there are differences between the disciplines in terms of how much equipment there is and how it is distributed. The whole notion of grid computing arose from the realisation that physics data couldn't possibly be processed on a few machines in one place. Although the LHC is a special case, it drove the need for grid computing with an annual output that dwarfs the 40GB number you mention (by around a millionfold). And it isn't likely that the physicists will leave it at that: I'm sure they have lots of smaller experiments that generate plenty of data, too. As always, it's worth looking over their shoulders and picking up some ideas.

Posted by Titus Brown on 2010-10-16 at 20:08.

Deepak, agreed. Paul, the democritization of sequencing capacity (to the point where each lab is generating their own Medium Data, and doing so on a regular and continuing basis) **does** make it different from physics, I believe. (I work with a lot of physicists, albeit not from particle.) Physics has done a pretty good job of coordinating some critical aspects of its data analysis (be it software library production, or infrastructure investment) but I don't expect to see the same thing happening in biology, both because of the cottage industry nature of sequencing data and because of the culture. Once you reach the point where a single lab can generate 10 Tb of sequencing data in a week, and there are 1,000 labs doing this on a regular basis, it **is** different from anything I've seen before.I'd love to be proven wrong! The bigger cultural issues are really problematic, with most biologists posessing very little interest in numerical thinking, computational science, or data analysis.

Posted by Pat Schloss on 2010-10-18 at 09:59.

I would agree with most of what's been said, but I would add a couple of other points... 1. Much of the discussion seems to assume that there is infinite biodiversity out there. I got this from people as I set up analyzing the 90 million 16S reads for the HMP - something to the effect that "90 million will be hundreds of times harder than processing 1 million sequences". The fact was that it wasn't much harder/slower at all as long as the code is well programmed and **the data were good**. At least with Titanium, the last 200 bp of the reads are junk for our purposes and artificially jack up the number of unique sequences. If you only work on the uniques, then this will be hard. I suspect with metagenomics, if people actually cared about data quality, assembly might be easier. Furthermore, as we exponentially increase the number of reads, assembly **should** get better making other things easier. 2. It's all about the questions. Everyone is crazed by cheap sequencing without actually considering whether they need it to answer their biological question. They also do analyses without thinking about their questions. For example, most assemblers gag by unevenly sampled genomic regions that we see constantly in metagenomics. But the biggest problem, imho is designing studies that don't have questions (i.e. the HMP) and then expecting everyone to pick out data that are next to impossible to analyze and generated from poorly designed experiments.

Posted by Titus Brown on 2010-10-18 at 13:03.

Hi Pat! Re #1, yes, I'm already seeing saturation in mRNAseq. It screws up assembly differently, but of course it's certainly more scalable! But I don't think we'll see saturation in soil for quite a while (2-5 years at least). #2, of course. But the fact remains that there **are** a lot of questions that can be addressed with the help of cheap sequencing, and they're going to asked, and it would be nice to be able to answer them, at least partially!

Posted by Titus Brown on 2010-10-20 at 10:12.

A good post on the storage issues: <a href="http://www.bio- itworld.com/2010/10/07/storage.html">http://www.bio- itworld.com/2010/10/07/storage.html</a>

Comments !