I've spent the last few weeks working on a simple solution to a challenging problem in DNA sequence assembly, and I think we've got a nice simple theoretical solution with an actual implementation. I'd be interested in comments!

Introduction

Briefly, the algorithmic challenge is this:

We have a bunch of DNA sequences in (let's say) FASTA format,

>850:2:1:1145:4509/1 CCGAGTCGTTTCGGAGGGACCCCGCCATCATACTCGGGGAATTCATCTGAAAGCATGATCATAGAGTCACCGAGCA >850:2:1:1145:4509/2 AGCCAAGAGCACCCCAGCTATTCCTCCCGGACTTCATAACGTAACGGCCTACCTCGCCATTAAGACTGCGGCGGAG >850:2:1:1145:14575/1 GACGCAAAAGTAATCGTTTTTTGGGAACATGTTTTCATCCTGATCATGTTCCTGCCGATTCTGATCTCGCGACTGG >850:2:1:1145:14575/2 TAACGGGCTGAATGTTCAGGACCACGTTTACTACCGTCGGGTTGCCATACTTCAACGCCAGCGTGAAAAAGAACGT >850:2:1:1145:2219/1 GAAGACAGAGTGGTCGAAAGCTATCAGACGCGATGCCTAACGGCATTTTGTAGGGCGTCTGCGTCAGACGCCAACC >850:2:1:1145:2219/2 GAAGGCGGGTAATGTCCGACAAACATTTGACGTCAAAGCCGGCTTTTTTGTAGTGGGTTTGACTCTTTCGCTTCCG >850:2:1:1145:5660/1 GATGGCGTCGTCCGGGTGCCCTGGTGGAAGTTGCGGGGATGCGGATTCATCCGGGACGCGCAGACGCAGGCGGTGG

and we want to pre-filter these sequences so that only sequences containing high-abundance DNA words of length k ("k-mers"), remain. For example, given a set of DNA sequences, we might want to remove any sequence that does not contain a k-mer present at least 5 times in the entire data set.

This is very straightforward to do for small numbers of sequences, or for small k. Unfortunately, we are increasingly confronted by data sets containing 250 million sequences (or more), and we would like to be able to do this for large k (k > 20, at least).

You can break the problem down into two basic steps: first, counting k-mers; and second, filtering sequences based on those k-mer counts. It's not immediately obvious how you would parallelize this task: the counting should be very quick (basically, it's I/O bound) while the filtering is going to rely on wide-reaching lookups that aren't localized to any subset of k-mer space.

tl; dr? we've developed a way to do this for arbitrary k, in linear time and constant memory, efficiently utilizing as many computers as you have available. It's open source and works today, but, uhh, could use some documentation...

Digression: the bioinformatics motivation

(You can skip this if you're not interested in the biological motivation ;)

What we really want to do with this kind of data is assemble it, using a De Bruijn graph approach a la Velvet, ABySS, or SOAPdenovo. However, De Bruijn graphs all rely on building a graph of overlapping k-mers in memory, which means that their memory usage scales as a function of the number of unique k-mers. This is good in general, but Bad in certain circumstances -- in particular, whenever the data set you're trying to assemble has a lot of genomic novelty. (See this fantastic review and my assembly lecture for some background here.)

One particular circumstance in which De Bruijn graph-based assemblers flail is in metagenomics, the isolation and sequencing of genetic material from "the wild", e.g. soil or the human gut. This is largely because the diversity of bacteria present in soil is so huge (although the relatively high error rate of next-gen platforms doesn't help).

Prefiltering can help reduce this memory usage by removing erroneous sequences as well as not-so-useful sequences. First, any sequence arising as the result of a sequencing error is going to be extremely rare, and abundance filtering will remove those. Second, genuinely "rare" (shallowly-sequenced) sequences will generally not contribute much to the assembly, and so removing them is a good heuristic for reducing memory usage.

We are currently playing with dozens (probably hundreds, soon) of gigabytes of metagenomic data, and we really need to do this prefiltering in order to have a chance at getting a useful assembly out of it.

It's worth noting that this is in no way an original thought: in particular, the Beijing Genome Institute (BGI) did this kind of prefiltering in their landmark Human Microbiome paper (ref). We want to do it, too, and the BGI wasn't obliging enough to give us source code (booooooo hisssssssssssssss).

Existing approaches

Existing approaches are inadequate to our needs, as far as we can tell from a literature survey and private conversations. Everyone seems to rely on big-RAM machines, which are nice if you have them, but shouldn't be necessary.

There are two basic approaches.

First, you can build a large table in memory, and then map k-mers into it. This involves writing a simple hash function that converts DNA words into numbers. However, this approach scales poorly with k: for example, there are 4**k unique DNA sequences of length k (or roughly (4**k) / 2 + (4**(k/2))/2, considering reverse complements). So the table for k=17 needs 4**17 entries -- that's 17 gb at 1 byte per counter, which stretches the memory of cheaply available commodity hardware. And we want to use bigger k than 17 -- most assemblers will be more effective for longer k, because it's more specific. (We've been using k values between 30 and 70 for our assemblies, and we'd like to filter on the same k.)

Second, you can observe that k-mer space (for sufficiently large k) is likely to be quite sparsely occupied -- after all, there's only so many actual 30-mers present in a 100gb data set! So, you can do something clever like use a tree representation of k-mers and then attach counters to the end nodes of the tree (see, for example, tallymer. The problem here that you need to use pointers to connect nodes in the tree, which means that while the tree size is going to scale with the amount of novel k-mers -- ok! -- it's going to have a big constant in front of it -- bad!. In our experience this has been prohibitive for real metagenomic data filtering.

These seem to be the two dominant approaches, although if you don't need to actually count the k-mers but only assess presence or absence, you can use something like a Bloom filter -- for example, see Classification of DNA sequences using a Bloom filter, which uses Bloom filters to look for novel sequences (the exact opposite of what we want to do here!). References to other approaches welcome...

Note that you really, really, really want to avoid disk access by keeping everything in memory. These are ginormous data sets and we would like to be able to quickly explore different parameters and methods of sequence selection. So we want to come up with a good counting scheme for k-mers that involves relatively small amounts of memory and as little disk access as possible.

I think this is a really fun kind of problem, actually. The more clever you are, the more likely you are to come up with a completely inappropriate data structure, given the amount of data and the basic algorithmic requirements. It demands KISS! Read on...

An approximate approach to counting

So, we've come up with a solution that scales with the amount of genomic novelty, and efficiently uses your available memory. It can also make effective use of multiple computers (although not multiple processors). What is this magic approach?

Hash tables. Yep. Map k-mers into a fixed-size table (presumably one about as big as your available memory), and have the table entries be counters for k-mer abundance.

This is an obvious solution, except for one problem: collisions. The big problem with hash tables is that you're going to have collisions, wherein multiple k-mers are mapped into a single counting bin. Oh noes! The traditional way to deal with this is to keep track of each k-mer individually -- e.g. when there's a collision, use some sort of data structure (like a linked list) to track the actual k-mers that mapped to a particular bin. But now you're stuck with using gobs of memory to keep these structures around, because each collision requires a new pointer of some sort. It may be possible to get around this efficiently, but I'm not smart enough to figure out how.

Instead of becoming smarter, I reconfigured my brain to look at the problem differently. (Think Different?)

The big realization here is that collisions may not matter all that much. Consider the situation where you're filtering on a maximum abundance of 5 -- that is, you want at least one k-mer in each sequence to be present five or more times across the data set. Well, if you look at the hash bin for a specific k-mer and see the number 4, you immediately know that whether or not there are any collisions, that particular k-mer isn't present five or more times, and can be discarded! That is, the count for a particular hash bin is the sum of the (non-negative) individual counts for k-mers mapping to that bin, and hence that sum is an upper bound on any individual k-mer's abundance.

The tradeoff is false positives: as k-mer space fills up, the hash table is going to be hit by more and more collisions. In turn, more of the k-mers are going to be falsely reported as being over the minimum abundance, and more of the sequences will be kept. You can deal with this partly by doing iterative filtering with different prime hash table sizes, but that will be of limited utility if you have a really saturated hash table.

Note that the counting and filtering is still O(N), while the false positives grow as a function of k-mer space occupancy -- which is to say that the more diversity you have in your data, the more trouble you're in. That's going to be a problem no matter the approach, however.

You can see a simple example of approximate and iterative filtering here, for k=15 (a k-mer space of approximately 1 billion) and hash table sizes ranging from 50m to 100m. The curves all approach the correct final number of reads (which we can calculate exactly, for this data set) but some take longer than others. (The code for this is here.)

Making use of multiple computers

While I was working out the details of the (really simple) approximate counting approach, I was bugged by my inability to make effective use of all the juicy computers to which I have access. I don't have many big computers, but I do have lots of medium sized computers with memory in the ~10-20 gb range. How can I use them?

This is not a pleasantly parallel problem, for at least two reasons. First, it's I/O bound -- reading the DNA sequences in takes more time than breaking them down into k-mers and counting them. And since it's really memory bound -- you want to use the biggest hash table possible to minimize collisions -- it doesn't seem like using multiple processors on a single machine will help. Second, the hash table is going to be too big to effectively share between computers: 10-20 gb of data per computer is too much to send over the network. So what do we do?

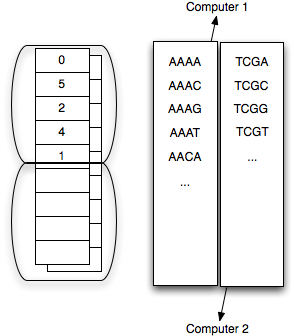

I was busy explaining to a colleague that this was impossible -- always a useful way for me to solve problems ;) -- when it hit me that you could use multiple chassis (RAM + CPU + disk) to decrease the false positive rate with only a small amount of communication overhead. Basically, my approach is to partition k-mer space into Z subsets (one for each chassis) and have each computer count only the k-mers that fall into their partition. Then, after the counting stage, each chassis records a max k-mer abundance per partition per sequence, and communicates that to a central node. This central node in turn calculates the max k-mer abundance across all partitions.

The partitioning trick is a more general form of the specific 'prefix' approach -- that is, separately count and get max abundances/sequence for all k-mers starting with 'A', then 'C', then 'G', and then 'T'. For each sequence you will then have four values (the max abundance/sequence for k-mers start with 'A', 'C', 'G', and 'T'), which can be cheaply stored on disk or in memory. Now you can do a single-pass integration and figure out what sequences to keep.

This approach effectively multiplies your working memory by a factor of Z, decreasing your false positive rate equivalently - no mean feat!

The communication load is significant but not prohibitive: replicate a read-only sequence data set across Z computers, and then communicate max values (1 byte for each sequence) back -- 50-500 mb of data per filtering round. The result of each filtering round can be returned to each node as a readmask against the already-replicated initial sequence set, with one bit per sequence for ignore or process. You can even do it on a single computer, with a local hard drive, in multiple iterations.

You can see a simple in-memory implementation of this approach here, and some tests here. I've implemented this using readmask tables and min/max tables (serializable data structures) more generally, too; see "the actual code", below.

Similar approaches

By allowing for false positives, I've effectively turned the hash table into a probabilistic data structure. The closest analog I've seen is the Bloom filter which records presence/absence information using multiple hash functions for arbitrary k. The hash approach outlined above devolves into a maximally efficient Bloom filter for fixed k when only presence/absence information is recorded.

The actual code

Theory and practice are the same, in theory. In practice, of course, they differ. A whole host of minor interface and implementation design decisions needed to be made. The result can be seen at the 'khmer' project, here: http://github.com/ctb/khmer. It's slim on documentation, but there are some example scripts and a reasonable amount of tests. It requires nothing but Python 2.6 and a compiler; nose if you want to run the tests.

The implementation is in C++ with a Python wrapper, much like the paircomp and motility software packages.

It will filter 1m 70-mer sequences in about 45 seconds, and 80 million sequences in less than an hour, on a 3 GHz Xeon with 16 gbs of RAM.

Right now it's limited to k <= 32, because we encode each DNA k-mer in a 64-bit 'long long'.

You can see an exact filtering script here: http://github.com/ctb/khmer/blob/master/scripts/filter-exact.py . By varying the hash table size (second arg to new_hashtable) you can turn it into an inexact filtering script quite easily.

Drop me a note if you want help using the code, or a specific example. We're planning to write documentation, doctests, examples, robust command line scripts, etc. prior to publication, but for now we're primarily trying to use it.

Other uses

It has not escaped our notice that you can use this approach for a bunch of other k-mer based problems, such as repeat discovery and calculating abundance distributions... but right now we're focused on actually using it for filtering metagenomic data sets prior to assembly.

Acks

I talked a fair bit with Prof. Rich Enbody about this approach, and he did a wonderful job of double-checking my intuition. Jason Pell and Qingpeng Zhang are co-authors on this project; in particular, Jason helped write the C++ code, and Qingpeng has been working with k-mers in general and tallymer in specific on some other projects, and provided a lot of background help.

Conclusions

We've taken a previously hard problem and made it practically solvable: we can filter ~88m sequences in a few hours on a single-processor computer with only 16gb of RAM. This seems useful.

Our main challenge now is to come up with a better hashing function. Our current hash function is not uniform, even for a uniform distribution of k-mers, because of the way it handles reverse complements.

The approach scales reasonably nicely. Doubling the amount of data doubles the compute time. However, if you have double the novelty, you'll need to do double the partitions to keep the same false positive rate, in which case you quadruple the compute time. So it's O(N^2) for the worst case (unending novelty) but should be something better for real-world cases. That's what we'll be looking at over the next few months.

I haven't done enough background reading to figure out if our approach is particularly novel, although in the space of bioinformatics it seems to be reasonably so. That's less important than actually solving our problem, but it would be nice to punch the "publication" ticket if possible. We're thinking of writing it up and sending it to BMC Bioinformatics, although suggestions are welcome.

It would be particularly ironic if the first publication from my lab was this computer science-y, given that I have no degrees in CS and am in the CS department by kind of a fluke of the hiring process ;).

Legacy Comments

Posted by Will Dampier on 2010-07-07 at 11:59.

Pretty cool work. I've actually implemented simple version of K-mer counting using Python's defaultdict data-structure ... although this won't scale to the sheer size of sequences that you're talking about. I seem to remember seeing a "rolling hash" designed for DNA sequences to reduce collisions and improve speed but for the life of me I can't find the paper. I'm sure a literature search will turn it up somewhere. Good luck, Will

Posted by Titus Brown on 2010-07-07 at 12:31.

Will, we're using a rolling hash fn for computing the hashes for long DNA strings, of course. Here's a blog post on a slightly different tactic: <a href="http://philatwarrimoo.blogspot.com/2010/04/simple- rolling-hash-part-3.html">http://philatwarrimoo.blogspot.com/2010/04 /simple-rolling-hash-part-3.html</a> looking at fast substring matching, which I don't think applies here. I'll do a more thorough search later. thanks! --titus

Posted by mike on 2010-07-08 at 02:36.

It'd be worthwhile to post a test reference data set. That way some of us could try out ideas on the same data and see how we go...

Posted by j_king on 2010-07-09 at 11:18.

An exciting post! I love these kinds of computing problems. Just a cursory note, but from a certain fuzzy perspective it looks almost like you've implemented a map-reduce pattern. Am I far off? Thanks for the post. :)

Posted by Titus Brown on 2010-07-10 at 09:52.

mike, you can download a data set here: <a href="http://angus.ged.msu.edu.s3.amazonaws.com/88m- reads.fa.gz">http://angus.ged.msu.edu.s3.amazonaws.com/88m- reads.fa.gz</a> It's got 88m reads, and unzips to about 10gb. Have fun ;) j_king, the partitioning of k-mer space does permit a kind of map-reduce, but the data that needs to be communicated back and forth is large enough that I don't think it fits that well. It's a pretty different problem, I think.

Posted by Paul Harrison on 2010-07-11 at 20:52.

I've experimented with k-mer counting a little. <a href="http://bioin formatics.net.au/software.nesoni.shtml">http://bioinformatics.net.au/s oftware.nesoni.shtml</a> My approach to k-mer counting uses a disk- based merge-sort like algorithm. With a little juggling, the whole problem can be transformed into something that only requires in-order disk access. When we are writing, we just dump everything into an unsorted list, then merge-sort it later. So for data sets larger than memory, the fast operations available are in-order reads and random writes. Step 1: scan reads in order, use merge-sort to make an index from kmers to reads. Step 2: scan kmer->read index in order, use merge-sort to make an index from reads to the counts of k-mers they contain. Step 3: scan reads and read->kmer-count index in parallel, in order, clipping based on k-mer counts.

Posted by j_king on 2010-07-12 at 12:54.

Thanks for the note, I'll check out the source. Cheers.

Posted by Titus Brown on 2010-07-12 at 14:06.

Hey Paul, thanks for the note! Do you have a rough sense of how fast that approach is, and what the memory requirements are? thanks, --titus

Comments !