I've been doing some more focused bioinformatics programming recently, and as I'm thinking about how to teach biologists about data analysis, I realize more and more how much backstory goes into even relatively simple programming.

The problem: given a reference genome, and a very large set of short, error-prone, random sequences from an individual (with a slightly different genome) aligned to that genome, find all differences and provide enough summary information that probably-real differences can be distinguished from differences due only to error. More explicitly, if I have a sequence to which a bunch of shorter sequences have been aligned, like so:

GAGGGCTACAAAAGGAGGCATAGGACCGATAGGACAT (reference genome)

GGCTAC -HWI-EAS216_0019:6:44:8736:13789#0/1[0:6]

GGCTAAA HWI-EAS216_0019:6:11:12331:10539#0/1[28:35]

GGCTAAAAA HWI-EAS216_0019:6:54:3745:18270#0/1[26:35]

GGCTAAAAAA HWI-EAS216_0019:6:75:4175:16939#0/1[25:35]

GGATACAACAG -HWI-EAS216_0019:6:96:16613:3276#0/1[0:11]

GGCTAAAAAAA HWI-EAS216_0019:6:11:8510:9363#0/1[22:33]

GGCTAAAAAAA HWI-EAS216_0019:6:72:14343:19416#0/1[21:32]

GGCTACAACAG -HWI-EAS216_0019:6:116:10526:5940#0/1[4:15]

GGCTAAAACAA HWI-EAS216_0019:6:103:9198:1208#0/1[18:29]

GGCTACAACAG -HWI-EAS216_0019:6:50:14928:13905#0/1[7:18]

GGCTACAACAG -HWI-EAS216_0019:6:109:18796:4787#0/1[14:25]

GGCTACAACAG -HWI-EAS216_0019:6:102:14050:8429#0/1[18:29]

GGCTACAACAG -HWI-EAS216_0019:6:22:14814:10742#0/1[23:34]

GCTCCACCAG -HWI-EAS216_0019:6:106:8241:6484#0/1[25:35]

TACAACAG HWI-EAS216_0019:6:4:8095:15474#0/1[0:8]

CAACAG HWI-EAS216_0019:6:115:15766:4844#0/1[0:6]

* ** * *

1 23 4 5

how do you gather all of the locations with differences, and then figure out which differences are significant? (Variations in 1 and 2 are probably errors, 4 and 5 may be real, and 3 is pretty clearly real, I would say.)

The numbers here aren't trivial: you're looking at ~1 million-3 billion bases for the reference genome, and 20-120 million or more shorter resequencing reads.

The first thing to point out is that it's not enough to simply look at all of the aligned sequences individually; you need to know how many total sequences are aligned to each spot, and what each nucleotide is. This is because the new sequences are error-prone: observing a single variation isn't enough, you need to know that it's systematic variation. So it's a total-information situation, and hence not just pleasantly parallel: you need to integrate the information afterwards.

I came up with two basic approaches: you can first figure out where there's any variation, and then iterate again over the short sequences, figure out which ones overlap detected variation, and record those counts; or you can figure out where there's variation, index the short sequences by position, and then query them by position. Both are easy to code.

For the first, approach A:

for seq, location in aligned_short_sequences:

record_variation(genome[location])

for seq, location in aligned_short_sequences:

if has_variation(location):

record_nucleotide(genome[location], seq)

For the second, approach B:

for seq, location in aligned_short_sequences:

record_variation(genome[location])

for location in recorded_variation:

aligned_subset = get_aligned_short_sequences(location)

for seq, _ in aligned_subset:

record_nucleotide(genome[location], seq)

It's readily apparent that barring stupidity, approach A is generally going to be faster: there's one less loop, for one thing. Also, if you think about implementation details, approach B is potentially going to involve retrieving aligned short sequences multiple times, while approach A looks at each aligned short sequence exactly once.

However, there are tradeoffs, especially if you're building tools to support either approach. The most obvious one is, what if you need to look at variation on less than a whole-genome level? For example, for visualization, or gene overlap calculations, you're probably not going to care about an immense region of the genome; you may want to zoom in on a few hundred bases. In that case, you'd want to use some of the tools from approach B: given a position, what aligns there?

if variation_at(genome[location]):

aligned_subset = get_aligned_short_sequences(location)

for seq, _ in aligned_subset:

record_nucleotide(genome[location], seq)

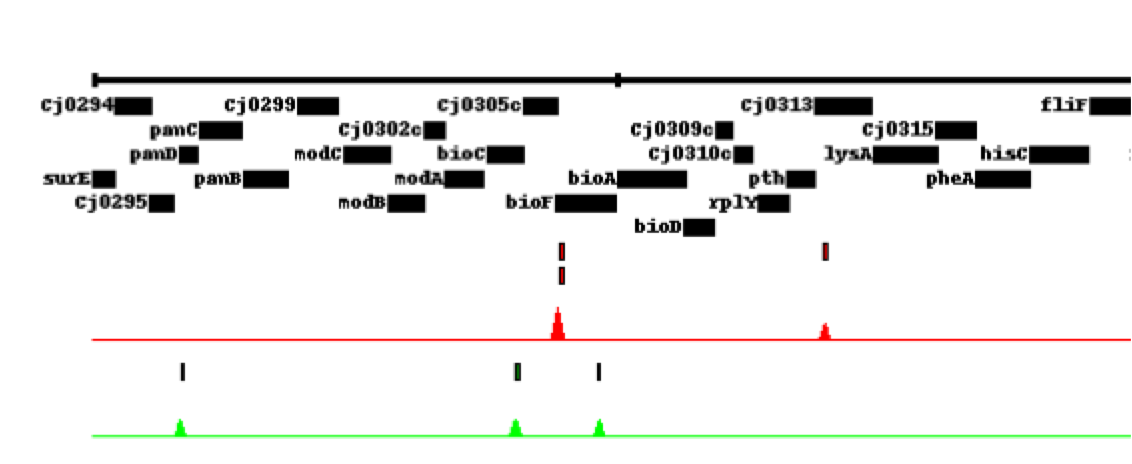

Another tradeoff is simply whether or not to store everything in memory (fast) or on disk (slower, but scales to bigger data sets) -- I first wrote this code using an in-memory set, to look at low-variation chicken genome resequencing. Then, when I tried to apply it to a high variation Drosophila data set and a deeply sequenced Campylobacter data set, it consumed a lot of RAM. So you have to think about whether or not you want a single tool that works across all these situations, and if so, how you want it to behave for large genomes, with lots of real variation, and extremely deep sequencing -- plan for the worst, in other words.

I also tend to worry about correctness. Is the code giving you the right results, and how easy is it to understand? Each approach has different drawbacks, and relies on different bodies of code that make certain operations easy and other operations hard.

The upshot is that I wrote several programs implementing different approaches, and tried them out on different data sets, and chose the fastest one for one purpose (overall statistics) and a slower one for visualization. And most programmers I know would have done the same: tried a few different approaches, benchmarked them, and chosen the right tool for the current job.

Where does this leave people who don't intuitively understand the difference between the algorithms, and don't really understand what the tools are doing underneath, and why one tool might return different results (based on the parameters given) than another? How do you explain that sort of thing in a short amount of time?

I don't know, but it's going to be interesting to find out...

BTW, the proper way to do this is with pygr will someday soon be:

for seq, location in aligned_short_sequences: record_variation(genome[location]) mapping = index_short_sequences() results = intersect_mappings(variations, mapping)

where 'intersect_mappings' uses internal knowlege of the data structures to do everything quickly and correctly. That day is still a few months off...

--titus

Comments !