This March, Andreas Hejnol invited me to give a talk in Bergen, Norway, and as part of the trip I arranged to also give a trial workshop on "computational reproducibility" at the University in Oslo, where my friend & colleague Lex Nederbragt works.

(The workshop materials are here, under CC0.)

The basic idea of this workshop followed from recent conversations with Jonah Duckles (Executive Director, Software Carpentry) and Tracy Teal (Executive Director, Data Carpentry), where we'd discussed the observation that many experienced computational biologists had chosen a fairly restricted set of tools for building highly reproducible scientific workflows. Since Software Carpentry and Data Carpentry taught most of these tools, I thought that we might start putting together a "next steps" lesson showing how to efficiently and effectively combine these tools for fun and profit and better science

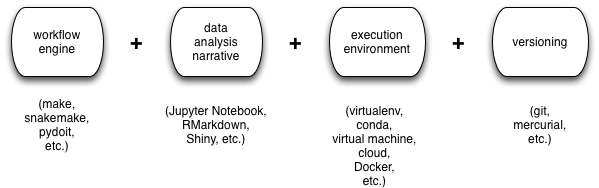

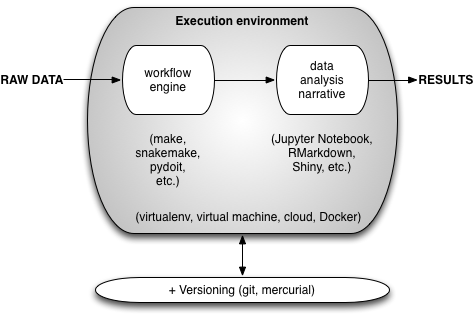

The tool categories are as follows: version control (git or hg), a build system to coordinate running a bunch of scripts (make or snakemake, typically), a literate data analysis and graphing system to make figures (R and RMarkdown, or Python and Jupyter), and some form of execution environment (virtualenv, virtual machines, cloud machines, and/or Docker, typically). There are many different choices here - I've only listed the ones I run across regularly - and everyone has their own favorites, but those are the categories I see.

These tools generally work together in some fashion like this:

In the end, the 1-day workshop description I sent Lex was:

Reproducibility of computational research can be achieved by connecting together tools that many people already know. This workshop will walk attendees through combining RMarkdown/Jupyter, git (version control), and make (workflow automation) for building highly reproducible analyses of biological data. We will also introduce Docker as a method for specifying your computational environment, and demonstrate mybinder.org for posting computational analyses. The workshop will be interactive and hands-on, with many opportunities for questions and discussion. We suggest that attendees have some experience with the UNIX shell, either Python or R, and git - a Software or Data Carpentry workshop will suffice. People will need an installation of Docker on their laptop (or access to the Amazon Cloud).

From this, you can probably infer that what I was planning on teaching was how to use a local Docker container to combine git, make, and Jupyter Notebook to do a simple analysis.

As the time approached (well, on the way to Oslo :) I started to think concretely about this, and I found myself blocking on two issues:

First, I had never tried to get a whole classroom of people to run Docker before. I've run several Docker workshops, but always in circumstances where I had more backup (either AWS, or experienced users willing to fail a lot). How, in a single day, could I get a whole classroom of people through Docker, git, make, and Jupyter Notebook? Especially when the Jupyter docker container required a large download and a decent machine and would probably break on many laptops?

Second, I realized I was developing a distaste for the term 'reproducibility', because of the confusion around what it meant. Computational people tend to talk about reproducibility in one sense - 'is the bug reproducible?' - while scientists tend to talk about reproducibility in the larger sense of scientific reproducibility - 'do other labs see the same thing I saw?' You can't really teach scientific reproducibility in a hands-on way, but it is what scientists are interested in; while computational reproducibility is useful for several reasons, but doesn't have an obvious connection to scientific reproducibility.

Luckily, I'd already come across a solution to the first issue the previous week, when I ran a workshop at UC Davis on Jupyter Notebook that relied 100% on the mybinder service - literally, no local install needed! We just ran everything on Google Compute Engine, on the Freeman Lab's dime. It worked pretty well, and I thought it would work here, too. So I resolved to do the first 80% or more of the workshop in the mybinder container, making use of Jupyter built-in Web editor and terminal to build Makefiles and post things to git. Then, given time, I could segue into Docker and show how to build a Docker container that could run the full git repository, including both make and the Jupyter notebook we wrote as part of the analysis pipeline.

The second issue was harder to resolve, because I wanted to bring things down to a really concrete level and then discuss them from there. What I ended up doing was writing a moderately lengthy introduction on my perspective, in which I further confused the issue by using the term 'repeatability' for completely automated analyses that could be run exactly as written by anyone. You can read more about it here. (Tip o' the hat to Victoria Stodden for several of the arguments I wrote up, as well as a pointer to the term 'repeatability'.)

At the actual workshop, we started with a discussion about the goals and techniques of repeatability in computational work. This occupied us for about an hour, and involved about half of the class; there were some very experienced (and very passionate) scientists in the room, which made it a great learning experience for everyone involved, including me! We discussed how different scientific domains thought differently about repeatability, reproducibility, and publishing methods, and tentatively reached the solid conclusion that this was a very complicated area of science ;). However, the discussion served its purpose, I think: no one was under any illusions that I was trying to solve the reproducibility problem with the workshop, and everyone understood that I was simply showing how to combine tools to build a perfectly repeatable workflow.

We then moved on to a walkthrough of Jupyter Notebook, followed by the first two parts of the make tutorial. We took our resulting Makefile, our scripts, and our data, and committed them to git and pushed them to github (see my repo). Then we took a lunch break.

In the afternoon, we built a Jupyter Notebook that did some silly graphing. (Note to self: word clouds are cute but probably not the most interesting thing to show to scientists! If I run this again, I'll probably do something like analyze Zipf's law graphically and then do a log-log fit.) We added that to the git repo, and then pushed that to github, and then I showed how to use mybinder to spin the repo up in its own execution environment.

Finally, for the last ~hour, I sped ahead and demoed how to use docker-machine from my laptop to spin up a docker host on AWS, construct a basic Dockerfile starting from a base of jupyter/notebook, and then run the repo on a new container using that Dockerfile.

Throughout, we had a lot of discussion and (up until the Docker bit) I think everyone followed along pretty well.

In the end, I think the workshop went pretty well - so far, at least, 5/5 survey responders (of about 15 attendees) said it was a valuable use of their time.

After I left at 3pm to fly up to Bergen for my talk, Tracy Teal went through RMarkdown and knitr, starting from the work-in-progress Data Carpentry reproducibility lesson. (I didn't see that so I'll leave Lex or Tracy to talk about it.)

What would I change next time?

- I'm not sure if the Jupyter Notebook walkthrough was important. It seemed a bit tedious to me, but maybe that was because it was the second time in two weeks I was teaching it?

- I shortchanged make a bit, but still got the essential bits across (the dependency graph, and the basic Makefile format).

- I would definitely have liked to get people more hands-on experience with Docker.

- I would change the Jupyter notebook analysis to be a bit more science-y, with some graphing and fitting. It doesn't really matter if it's a bit more complicated, since we're copy/pasting, but I think it would be more relevant to the scientists.

- I would try to more organically introduce RMarkdown as a substitute for the Jupyter bit.

Overall, I'm quite happy with the whole thing, and mybinder continues to work astonishingly well for me.

-titus

Comments !